When somebody asks you how you are, what do you base your reply on?

If you’re being honest (and not just following the social convention of saying “good, what about you?”), you probably check in with yourself and give a reply based on how you are in that moment.

However, the question was not “How are you in this moment?”. The question was simply “How are you?”. Yet we usually let the answer to that question be defined by the moment we are in.

It’s a subtle distinction. And you could ask yourself, why does it even matter?

Because depending on the breadth of your perspective when answering this question, your answers will be different.

And other people are not the only ones asking the question. We all want to be happy (most of us at least). So consciously or unconsciously, we often ask ourselves how we are doing to gauge what our current happiness level is. And we base how we feel on our perception of that happiness level.

• If the answer is “bad”, we feel bad.

• If the answer is “good”, we feel good.

• If the answer is “good, but still some small aspect could be better”, we feel motivated to make a change.

You could argue that the actual feeling comes before the answer, and that’s exactly why you give such an answer. Maybe it does. But the answer definitely re-affirms the feeling and thus creates more of it. So it’s really more a chicken vs. egg situation. If you don’t believe me, try the experiment from this article.

Narrow vs. Wide Perspective

Last year my father passed away. This obviously had a big impact on “how I was doing”. Grief is unpredictable both in terms of what you will feel, how long you will feel it, and when you will feel it.

As somebody who is usually very much in control of his own emotional state, this bothered me. When I feel bad about something, my go to approach is to fix it and feel better again. Grief is a different emotional beast. While it’s one thing to find intellectual peace with the fact that your dad doesn’t exist anymore, you still have to pass through all the psychological adjustments. You can’t just skip the process.

As a secondary consequence, I would feel bad about feeling bad. Because I was pre-occupied with processing these emotions, I’d find it impossible to bring my a-game to my work, art and relationships with others. Which would in turn reveal other insecurities or emotional wounds that would then re-start the cycle.

So whenever somebody asked me how I was doing, my answer -given from the narrow perspective of what I was experiencing in that moment- would not be very positive.

But interestingly, at the end of the year I was doing my yearly reflection (looking back at what I learned, who I’ve become and setting an intention and focus for the year to come), I saw a different picture.

I wanted to write about how bad I had been doing all year. But then I looked at the facts and saw that:

• I actually got a lot done. About as much as other years. Even though I had given up on trying to get anything done. It just sorta happened.

• We had traveled to a different country once a month give or take (some months without, some months with 2 trips)

• We had given many awesome parties, brought different people together and encouraged them to become more open

• I had learned a lot and had become way more mature as a person. Probably due to the fact that I no longer had a father.

There were definitely unbalanced periods. Some of my skills deteriorated because I had no energy to practice. I could spend a lot less time making money. Many relationships suffered due to my absence (or being in lesser shape). At times I also wasn’t nice to others because I was going through some stuff. And I learned a lot of personal lessons that made me grow in a direction that wasn’t always in sync with others.

But when I looked back now at the full scope of the year. It seems that in the bigger picture, things looked as balanced and healthy as every other year.

In fact, I could look at the same year behind me and instead of calling it “bad” -as I had done while it was happening- I could call it an amazing transformative year.

In fact, the wider my perspective becomes (the more I zoom out), the more I can see how exceptionally awesome this life is.

Judging the Wave By Its Peaks and Valleys

Life is cyclical. Every year it goes through the same seasonal changes. There is life and death and life again. There are inbreaths and outbreaths. Moon cycles. Mood cycles. Sleep cycles. Rhythms that decide when you feel awake or tired. Even rhythms that decide when you will make your next doodoo.

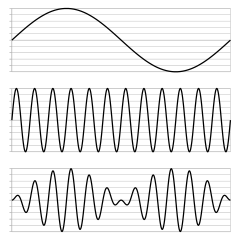

Let’s imagine for a moment that below are the frequencies of some of those rhythms:

For example, let’s say the rhythm on the bottom is your mood changes. When somebody would ask you how you were doing in one of the peaks, you’d say “Awesome!”. If they’d ask you in one of the valleys, you would say “Horrific!” But if you were to zoom out, you’d see that you were doing pretty neutral. In fact, when you look at the bigger picture, your entire cycle of moods seems to be pretty good.

While there are occasionally events that disrupt these cycles, in general I’ve noticed that the more you zoom out, the more you discover some kind of constant “baseline” emotion. The center line your emotional wave form revolves around.

I’d argue that this is how you’re really doing. The waves are more like inbreaths and outbreaths. Without outbreath, there can be no next inbreath. The peaks and valleys need each other to exist. If there were only peaks, it would be a flat line again. And since life is cyclical, a flatline equals death.

Disrupting the Waves

If you recognize these waves for what they are, you can also learn to accept them. Since you know every valley will pass and become a peak again any way.

But when you try to resist the low parts of the wave, they become stronger and longer.

How does this work?

If you’re unwilling to accept any of the lower parts of the wave, you will create the need for every moment to be flawless. Which of course is an expectation that cannot be fulfilled. And what happens when you compare every day in your clearly cyclical life to an impossible standard of “only peaks”?

Your resistance to the movement of the wave creates deeper and longer valleys. You could compare this to ocean waves. They start underwater as a valley, then reach a peak that ehm… “peaks out” over the surface of the ocean (the midline).

Imagine that every ocean wave was somehow an object, like a beach ball. When a beach ball is deep underwater, it naturally wants to move up and “shoot out of the water”. Unless you push the beach ball down. That is what you are doing when you resist the movement of the wave. The wave is at the bottom. It wants to move up, but you’re pushing against it because you don’t like where it is right now. Ironically, it’s this pushing against the wave that keeps it stuck at the bottom.

But if you let the wave just do what it always does, things will soon feel good again. If you stop requiring every part of the wave to be “at the top” (which is impossible, or it ceases to be a wave), you’re giving it space to go up again.

If you let go and learn to surf/dance to those rhythms instead of resisting them, you start to feel more like the zoomed out perspective: Balanced.

And then, even when you’re feeling a bit shitty one day, you’ll still be able to honestly reply “I’m doing great.” Or at the worst, “I’m not in a good mood right now, but if I’m honest, things are pretty awesome.”